Tavern scene

Cristòfor Alandi (Terragona, 1856 – Barcelona, 1896)

Tavern scene

Oil on canvas, 155 x 120 cm

With frame, 166 x 133 cm

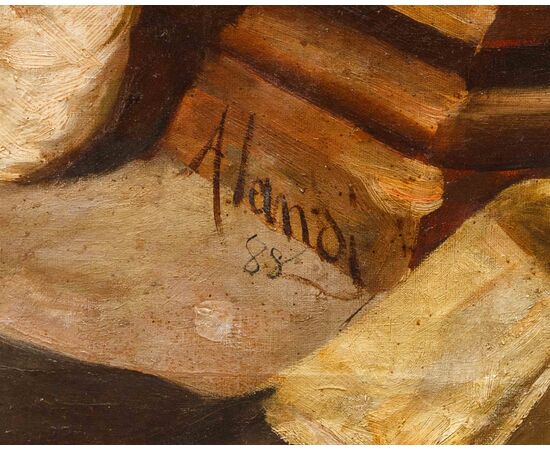

Signed and dated 1888 lower right

The painting under examination stands as a living testimony of the 19th century in Spain, a century of profound transformations and upheavals both politically and socially, which were reflected in artistic production and, in particular, in painting. The Spanish artists of this period, in fact, found themselves having to reconcile the pictorial traditions of the past with the new influences coming from Europe, giving rise to great experimentation. Specifically, Realism found fertile ground especially in the second half of the century, when people began to dedicate themselves more to the accurate representation of daily reality and its protagonists (peasants, shepherds, drinkers, gamblers, musicians, etc.), always adopting a critical eye and attention to detail.

The majestic canvas presented here is the work of one of the main exponents of 19th-century Spanish painting, Cristòfor (or Cristobal) Alandi (Terragona, 1856 – Barcelona, 1896), as evidenced by the signature affixed in the lower right. An artist of whom little biographical information is known, partly due to his premature death at the age of just forty, we know that he trained at the Academy of Fine Arts in Barcelona under the guidance of Simó Gomez Polo, a realist painter and engraver who had worked closely with the French Alexandre Cabanel, Tony Robert-Fleury, allowing himself to be deeply inspired by the masterpieces of Édouard Manet and Eugène Delacroix. At the age of eighteen, during a trip to Rome, he had the opportunity to see and learn about the works of the master Marià Fortuny i Marsal (Reus, 1838 – Rome, 1874), son-in-law of the director of the Prado Museum and undisputed model for many Spanish artists of the second half of the 19th century, whose art was characterized by pragmatic scenes of common life of great vivacity (to quote the words of the critic Théophile Gautier “Fortuny as an etcher equals Goya and approaches Rembrandt”).

Alandi repeatedly took up the models of the master, so much so that in 1879 he sent to Barcelona a copy of the Battle of Tetuan and one of the Battle of Wad-Ras, which attested to his great technical skill. After returning to Spain and studying at the San Fernando Higher School of Painting in Madrid, his fame began to spread widely, thanks also to his frequent participation in international Salons, which made him known to the general public: at the National Exhibition of Fine Arts in 1884 he presented the painting La pastora catalana; he subsequently participated in group exhibitions in the Parés hall in 1892 and in May 1893; he exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1893; he participated in the Exhibition of Fine Arts in Barcelona in 1894; in 1898, two years after his death, his work DélelTono (Giving it the tone) was published in the Album of the Salon.

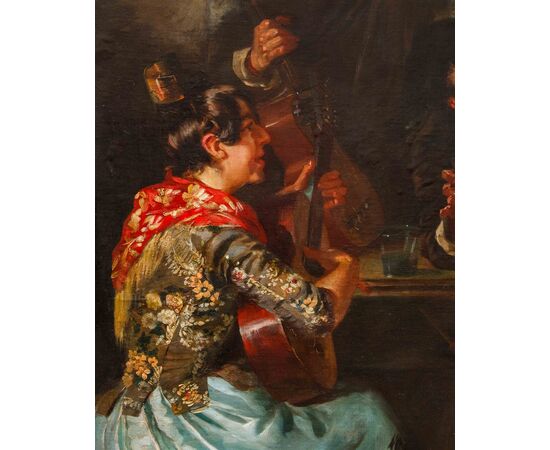

The canvas examined here, created by Alandi in 1888 at the age of thirty-two, shows a Tavern Scene in which two women are visible in the foreground, one sitting with her back turned intent on playing a guitar and the other facing with her gaze fixed on the viewer, and two men in the background, one always with the musical instrument in hand, caught while, bewitched by the female presence, brandishing their glasses of wine. Among the pioneers of realist painting in Spain, Alandi distinguishes himself here for an extraordinary ability to capture the essence and expressiveness of his subjects, through well-calibrated glances and poses. The brushstroke is thick, vibrant, free, with an absolute ability to render the pictorial material, but also intense and fluid, capable of simulating a lively dynamism. The contrast between light and shadow becomes a key element for understanding the painting: the artist, in fact, uses light to model the forms and create a sense of depth and three-dimensionality, made even more accentuated by the chromatic choice. From a dark background in the shadows, where earthy and brownish tones prevail, the two women emerge in all their power, struck directly by the beam of light, whose physiognomies recall the typical Hispanic traits. The two wonderful traditional Catalan dresses certainly do not go unnoticed, a strong symbol of cultural identity, on which Alandi concentrates all his attention: a colorful kaleidoscope of different fabrics, embroidery, lace and lace that has become iconic in Iberian folklore. His portraits, therefore, are not simple physical representations, but real cultural and social investigations.