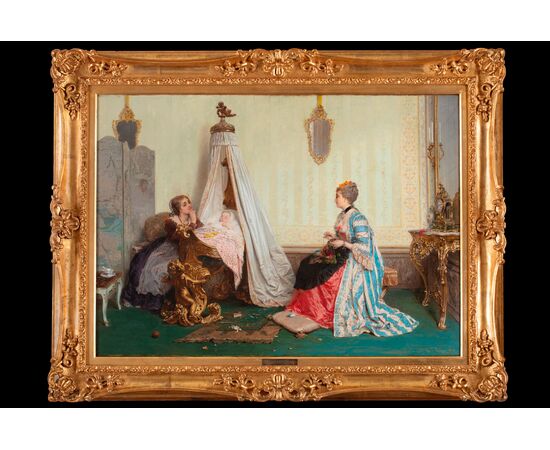

Gerolamo Induno (Milan, 1825 – 1890), "Maternal Joys", 1870

Gerolamo Induno (Milan 1825 – 1890), "Maternal Joys", 1870

Oil on canvas, 106 x 77 cm.

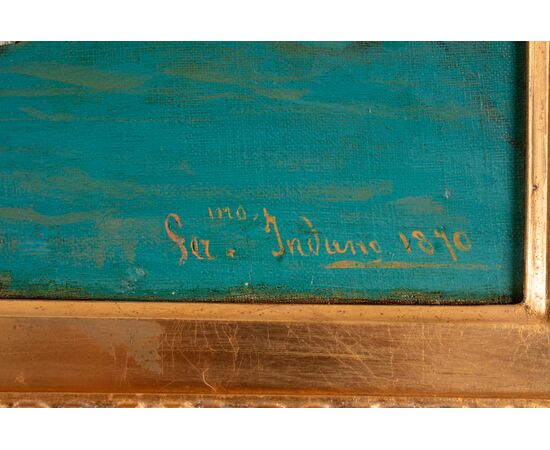

Signed "G. Induno" on the lower right.

The canvas Maternal Joys depicts a tender genre scene, set in a refined domestic environment of the mid-18th century.

At the center of the composition stands a sumptuous four-poster cradle, made of gilded wood and rocaille decorations, where a baby is softly resting. On the top and at the bottom, two sculpted angels stand out, a symbol of purity and protection, which give the scene a subtle spiritual dimension.

The mother of the child, the noblewoman on the right, is sitting composedly and, in the meantime, dedicates herself to the typically feminine art of embroidery, a gesture that highlights her role as guardian of the home. The powdered hair, the velvet choker, and the rich silk dress are evidence of her high social status, connecting with the refined surrounding environment.

Leaning over the cradle, we can see the wet nurse, whose clothing, more sober and composed, evokes a simple rural tradition without, however, taking away from the dignity of the figure. An embroidered apron encompasses her waist, her neck is adorned with a "garnet necklace"; on the nape of her neck, silver hairpins are arranged "in the manner of the rays of a halo". Certainly, Induno must have been inspired by the description of Lucia Mondella on her wedding day written by Manzoni. The wet nurse puts her finger to her lips, inviting silence, so as not to reawaken the newly dozed-off child.

The room is furnished with refinement and care, in full eighteenth-century taste, as demonstrated by the presence of a rococo console table, on which a pendulum clock rests. The Persian carpet, a small Chinese potiche, and the Japanese-style paper screen add an exotic and cultured touch. The presence of the latter reflects the interest in Japonisme, which in the second half of the nineteenth century began to spread even in Italy, influencing the furnishings and taste of the wealthiest classes.

The palette is warm and harmonious: it favors light and golden tones, such as the damask wallpaper of the walls; the wall mirrors reflect a natural and soft light, which envelops and delicately models the volumes, arousing a sense of protection and family warmth in the observer. The tones of gold and ivory converse with the earthy nuances of the wet nurse's clothing and, at the same time, highlight the bright colors worn by the noblewoman; the result is a harmonious and balanced composition.

Induno's brushstroke is uniform and measured, typical of 19th-century academic painting; a refined style, which embellishes and smoothes the figures and highlights the details.

In conclusion, the work is a very fine example of the artist's mastery, capable of combining formal elegance and narrative sensitivity.

BIOGRAPHY

Gerolamo Induno was born in Milan in 1825, from a family of humble origins. His older brother Domenico, whose talent had been discovered by the goldsmith Luigi Cossa, guided him right from the start in his artistic journey. He also enrolled at the Brera Academy, where he became a student of Luigi Sabatelli. His commitment guaranteed him remarkable academic recognition during the last two years of his course and, also in 1845, he presented himself for the first time at the annual Brera Exhibition with two portraits and studies from life.

After completing his academic career, he continued his apprenticeship with his brother, both influenced by Hayez's pictorial style. The strong patriotic sentiment of both of them pushed them to participate in the riots of the Five Days of Milan in 1848 and for this reason they were exiled to Canton Ticino. After moving to Florence the following year, he joined a group of volunteer patriots to defend the Roman Republic from the French; unfortunately, he remained seriously injured during a raid that kept him in bed.

During his convalescence, he began to paint the military events that he had experienced firsthand, creating a true visual chronicle of the Risorgimento such as Garibaldini on the defense of Rome, Garibaldi on the Gianicolo and the Portrait of Anita Garibaldi, created in 1849 and now kept at the Museum of the Risorgimento in Milan. Returning to his hometown, he continued to work in his brother's studio, participating in the Braidensi Exhibitions and in 1851 at the Promotrice of Turin with Sentinel.

The following year, Induno approached genre painting, participating in Brera with the painting The Storyteller; the short break from arms saw him participating in many exhibitions on national soil.

His patriotic spirit led him to enlist in the Piedmontese army and participate in the Crimean War, during which he produced sketches and drawings from life of the campaign; these notes inspired subsequent works, including the large canvas Battle of the Cernaia (1857), which King Vittorio Emanuele II purchased for the castle of Racconigi. Alongside works of a historical nature, he joined the production of genre scenes.

In 1859 he enlisted in the Cacciatori delle Alpi, a group led by Garibaldi; during the expeditions he resumed the now consolidated habit of providing a graphic chronicle of the facts. During this period, Induno tirelessly painted a conspicuous number of works with a Risorgimento theme with a celebratory character such as the Embarkation of the Thousand in Quarto or The Garibaldian's Farewell to His Mother, both from 1860. The following year the King commissioned him to execute the monumental and famous canvas The Battle of Magenta of June 4, 1859.

Also in this period he painted a series of canvases with a similar subject; the protagonists are young people who volunteer for the front. The paintings are particularly appreciated for their ability to represent, through the intimate episode of farewell to their loved ones, the popular involvement in the process of national unification.

There is no shortage of large public commissions, including in 1865 tempera paintings destined for the waiting room of the old central station in Milan, unfortunately lost.

The interest in the Risorgimento epic waned towards the end of the 1970s, when the wars of independence were but a distant memory; Induno crosses a final artistic phase, pervaded by a rediscovered fascination with the eighteenth century. The genre scenes become composed and elegant, the attention to detail an almost excessive display of his technical skill.

During the last years of his life he retired to Milan, where he continued to paint until his death in 1890.

Long forgotten by critics, he was then rediscovered almost a century after his death for his fundamental contribution to the iconography of the Risorgimento.