Pendant of paintings 'The Assault of the Brigands' 'After the Assault', Giuseppe Zais (Canale d'Agordo, Belluno 1709 - Treviso 1781)

Giuseppe Zais (Canale d'Agordo, Belluno 1709 - Treviso 1781)

Pendant of paintings

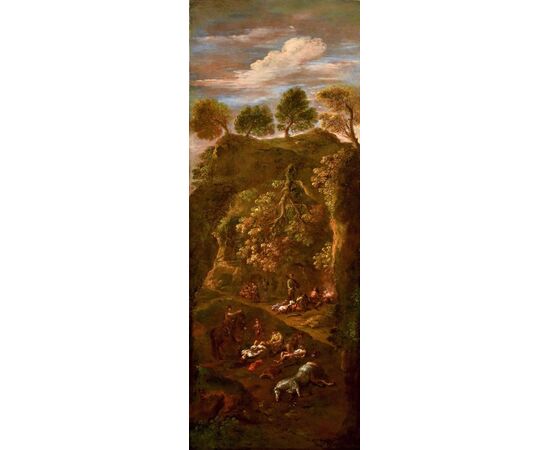

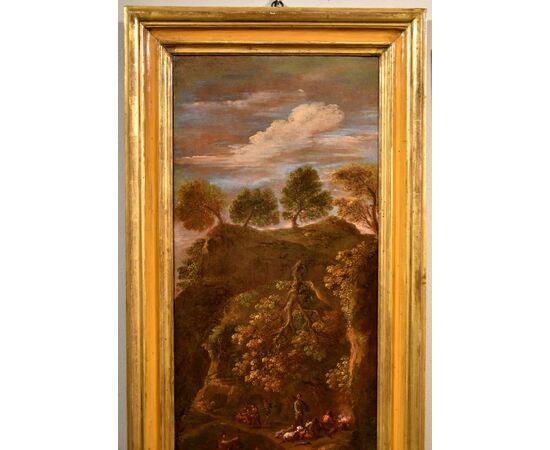

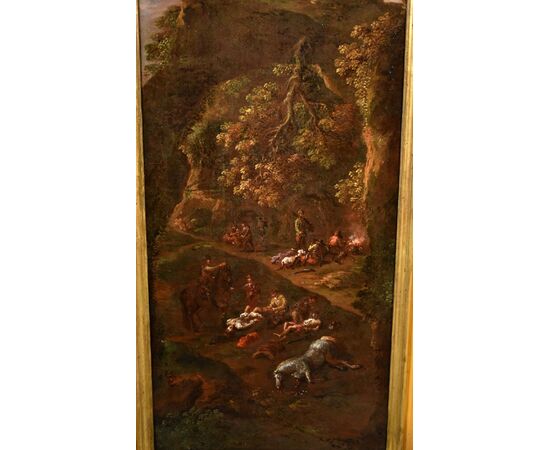

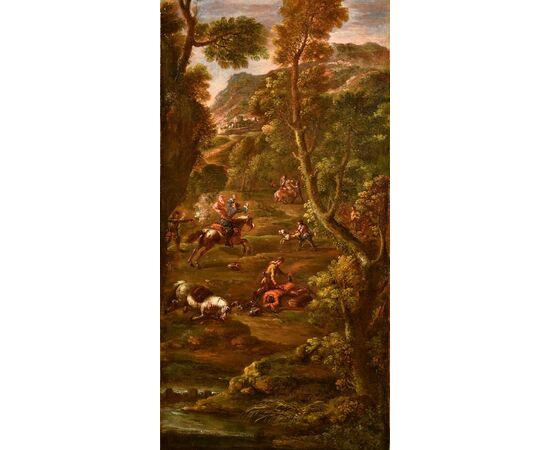

The Assault of the Brigands

After the Assault

&

Oil on canvas, 108 x 42 cm each.

Framed 128 x 62 cm.

&

We thank Doctor Federica Spadotto for having studied and traced the present pendant of paintings back to the catalogue of Giuseppe Zais. Below we propose the thorough critical study.

&

Details: link https://www.antichitacastelbarco.it/it/prodotto/giuseppe-zais--pendant-di-dipinti

The Venetian landscape of the golden age has accustomed the public and scholars to extraordinary - and unexpected - contaminations between genres, sealing an artistic stage that is very permeable to international suggestions. This undoubtedly happens because of the «foreign» origin linked to the rural repertoire, which records the fundamental contribution of transalpine referents (Spadotto, 2014) with regard to the inspiration and expressive alphabet of native artists.

Among the latter, the experience of Giuseppe Zais (Belluno 1709 - Treviso 1781) is fundamental, a painter who emigrated to the city of the lion presumably between the thirties and forties of the 17th century, where he would have carried out his apprenticeship with the battle painter Francesco Simonini (Parma, 1686- Venice or Florence, post 1755). In fact, it was an established practice for any painter who aspired to an official role - i.e. registration with the Fraglia - to practice alongside an established figure, such as the Parma master. Rather than a real apprenticeship, we must imagine the young painter active as a boy dealing with the war themes that had made Simonini famous in the Lagoon, where commissions flourished with the consequent need to entrust part of the work to a valid assistant (i.e. our Giuseppe).

Only recently, thanks to the pictorial essays made known by Egidio Martini, has a nucleus of paintings executed by Giuseppe (fig.1) been identified in close adherence to the repertoire of his master and which for a long time had been believed to be Simonini's autographs.

The analysis of these specimens highlights close affinities of form and style compared to those of Francesco, on which Zais grafts some guide characters that will become typical of his manner, among which the round tower and the characteristic physiognomy of the faces stand out.

Over the years, our artist will archive this experience in favour of Zuccarelli-inspired sunny afternoons, as well as collaborating with his son Gaetano (documented between 1765 and 1798) in his genre of choice. And a landscape made by the latter and made known by the writer (Spadotto, op.cit., 2014, fig.284, table XLV; fig.2) offers an important documentary piece to shed light on the extreme creative season of Nostro, passed over in silence by the sources and devoid of autograph works.

In the Landscape conceived with figures, statues and animals at the water trough (fig.2) Zais junior hands down a compendium of his father's production, expressed through a rather dense ductus and a chromatic grammar played on «earthy» tones, in line with the revival of Marco Ricci (Belluno, 1676-Venice, 1730) very much in vogue in the second half of the 18th century. Zuccarelli himself (Pitigliano, 1702-Florence, 1788) had also surrendered to the seduction of the Belluno artist, creating the Bull Hunt (fig.3) now at the Gallerie dell'Accademia in Venice, a true exemplum compared to the theme, where the same pictorial ingredients mentioned above emerge.

The notable pendant under examination fits into this horizon, which «displays» as a true testament to Giuseppe's long artistic journey, from his beginnings as a specialist in battles to the extreme synthesis of the late eighteenth century.

Simonini's soldiers become knights at the mercy of an attack by brigands, who kill them and strip them of all possessions, as happens in After the assault, in which the compositional layout of the post-battle camp hosts the outcome of the fatal crime, perpetrated by characters in whom we recognise the clothes and physiognomy of the villagers immortalized by Giuseppe in the famous rural passages.

The taste for detail, of clear Zuccarelli origin, merges with a fast, immediate style, which, however, does not betray the definition of the foliage in the typical, large trees called to frame the scenes, where the inspiration of the aforementioned Ricci merges with the northern European «fashion» established in Venetian figurative culture in the late eighteenth century.

Despite what the public's taste has expressed for most of the golden century, electing the languid Arcadian poetry as the territory of its aesthetic ideals, the decline of the Serenissima brings back the echoes of that «stepmother nature» frequented by the first generation of landscape painters, which returns, very relevant, as a metaphor for a world destined to die out a decade after his death.